BEYOND THE ONIROS FILM AWARDS®

VIP Interview with Igor Stephen Rados, director of the feature film ‘Nursery Rhyme of a Madman’

by Alice Lussiana Parente

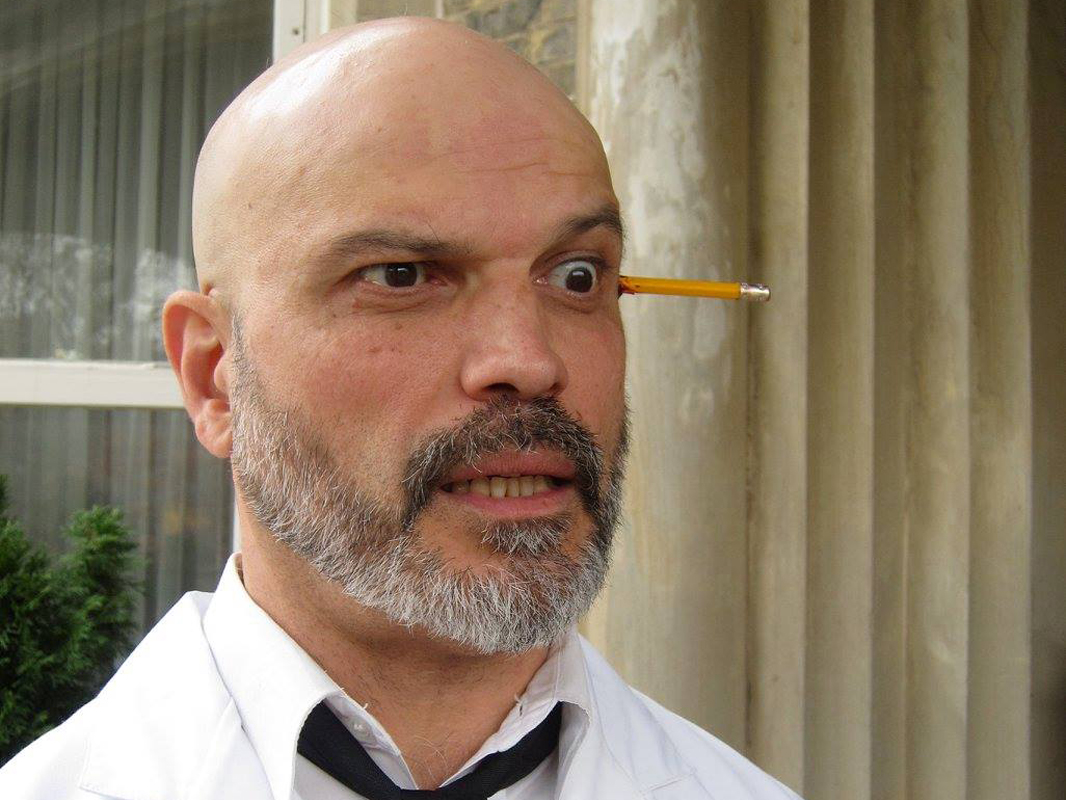

Today, we introduce Igor Stephen Rados, the director of the feature film Nursery Rhyme of a Madman. In this interview, we talk about the inspiration behind the script and the film industry in Toronto, and we dive into the meaning of realism in film and life.. As a famous band sings: Is this the real life. Is this just fantasy? Let’s find out!

Igor Stephen Rados, director of the feature film ‘Nursery Rhyme of a Madman’ – www.radosfilms.com

1. Hi Igor, it’s been a pleasure watching your work and congratulations on your award for Nursery Rhyme of a Madman. How did your career as a filmmaker begin?

Not just one point or event makes you want to become a filmmaker.

I got acquainted with films at three years old when my aunty and her Hungarian girlfriend took me to the theatre to watch Aldrich’s “Whatever Happened to Baby Jane”. That was back in Belgrade, Yugoslavia, where this film was a hit in the sixties. Those two ladies were sure we would be watching a sweet movie, or if not so much, I would be sleeping through the show.

They were wrong. It was a dark and scary movie, and I didn’t blink my eye. It was in English with Serbian subtitles. I didn’t understand a word, but the visuals, oh my god, the visuals… I was captivated. Nightmares have been chasing me for years. I had images of a ceramic-faced doll falling out of a car by the gate. I couldn’t understand where those pictures kept coming from, but I started falling in love with movies. Later in my teens, I’ve seen Rush’s film The Stunt Man with Peter O’Toole, playing an eccentric director. At that moment, I knew I wanted to be a filmmaker.

I came to Canada in 1988, graduated from the School of Business in 1994, began working on movie sets as a crew member, joined the Directors Guild of Canada, then graduated with Liberal Studies in Film and Theatre at York University in 1996 and Film Production with Honours in 1999, with an award-winning film called “Deja Vu-Deja Vu.”

That was a point of no return. I officially became a filmmaker, but If you asked me when and how my career began, it probably happened sometime at my birth.

2. Toronto is a very prolific film and tv location. How does living in such a vibrant city affect your work as a film director?

Toronto is a great city with a rich filmmaking tradition. It embraces all the cultures from around the world, making this city a tremendous artistic hub and a great pool of entertainment professionals and enthusiasts.

Hollywood industry widely extends to this city, not just for economic reasons but for great locations and excellent crew. Besides newly built studios, Toronto has thousands of restaurants, cafes, and nightclubs available as shooting locations. Neighbourhoods around the city offer a variety of possibilities. If you’re searching for a virtual look at Tokyo, New York, Miami, England, Middle East, you name it; you’ll find it in Toronto. The film crew in Toronto is well-trained and hard-working. The production unions such as IATSE, NABET, ACTRA, and DGC are all situated here to help and facilitate work in this town.

Independent artists can also find support through numerous media co-ops, art councils, affordable theatres, and film-loving sophisticated audiences. We often call ourselves “Hollywood North,” not just because we carry a lot of Hollywood productions but because of this city’s creative vibes and enthusiasm. After all, Toronto offers one of the greatest film festivals in the world every year. If you’re a serious film lover, you must visit TIFF.

3. You stated that for you – realism doesn’t simply exist – and this approach is clear throughout the whole film. Can you tell us explain this statement further?

Realism as a style certainly exists. It may be the most overrated and often reduced to a simple form that lost its attribute of the style. You may often see artists debating between style on one and realism on the other. Although as straightforward as it may look, the creation of it is a long road that will and must take us to another dimension.

Is it boredom, or is my reality twisted, or perhaps I like to push things to the next level? I deviate from realism to style whenever possible. Some texts call for it. If you treat them differently, you may end up with a poor banal piece.

It’s the directors’ job to put form to the story, but the style is what makes them great directors.

4. Considering this choice, what was the aspect and skills you were looking for when casting the actors?

I found that every actor can be used if placed well. The utmost quality I look for in them is the skill to listen. If an actor can take directions, we can work together, but if an actor can ad personal touch and bring the character to life, we can build a great movie.

5. How did you work with the actors on set? Did you give them space to improvise, or do you prefer to rehearse a scene before and achieve exactly what you had envisioned?

As a director, I learned to listen before I talk. I have my vision of the movie’s direction, but I like to hear what actors have to contribute to the show.

Making a movie is a collaborative process all the way. I like to see everyone being creative in their fields. My job as director is to bring the story to life and the actors to bring up the character. Often we tend to convey a personal agenda to work. We must respect the writer to stay in the same show.

Occasionally, I have to remind actors what the scene is about. Sometimes the character’s objective departs from the scene’s direction, but that’s okay. If done well, it will add a dramatic spice to it. For a film with a formal structure, I insist on rehearsals, not so much for performance, which should be the actor’s space, but for discoveries.

6. In the film, the two doctors trap the poet hoping to treat him with opposite approaches: a classic and a more revolutionary one. They reminded me a bit of a modern version of Jung and Freud. As an audience member, I couldn’t help myself wondering: who is truly the madman: the poet, the artist that is being held hostage, or the doctors?

The madness is all around us. The question is, on whom side are we?

Symbolism in the film is everywhere. Two doctors represent greed and opposing powers of the world. The poet represents art and creativity. The nurse stands for bleeding hearts and cultural needs. The inspector is part of the order and builders of society. The story’s irony is that everyone around the “sick” poet is more disturbed than the patient himself. The two doctors are the craziest.

7. Many authors of the past tackled the themes of mental illness in their books, including Edgar Allan Poe, F. Scott Fitzgerald among many others. What was the message you wanted to convey when writing the script and did any authors or filmmakers inspired you?

Our film derives from a short but powerful play, “Wariat i Zkonnica” by Polish playwright Stanislaw Ignacy Witkiewicz, known as “The Madman and The Nun.” The play was written around the Bolshevik Revolution as a solid response to notions of government to control social values, and art in particular. It was the point in history that ended freedom of expression. Art becomes a tool for the political needs of the government. In his play, the author pictures the world as a madhouse in a small box.

“Nursery Rhyme of a Madman” is not a straight adaptation but more an inspiration with segments of the script based on the play. I took the opportunity to translate the original text into a more adaptable form as the basis for a full-length screenplay. In addition, I embraced an impressionistic style with sparks of dark humour and magic realism to make this piece visually and conceptually unique.

The original text proceeds chronologically from dark comedy to tragedy and finally grotesque. The film shows the characters creating bizarre situations, dying, resurrecting, and losing their minds. The poet identifies his brain as a machine that never stops, even when asleep. “That’s why artists have to do crazy things,” he explains.

The chaotic bohemian life of an artist gets him trapped in an asylum. The final blow to his sanity is the death of his soul mate. He passionately expresses the desire to write himself to his demise. However, he ends up in the hands of a “caring society,” two enthusiastic experimental psychiatrists, who eventually drive him to a slow death.

The author brings an absurdist view of an artist in conflict with the state. It makes one wonder if the poet’s soulmate is ART itself, which dies at his hands.

8. The film gives a sense of claustrophobia, being all shot in the same and truly charming location. Where did you film it?

We shot the entire film in Toronto and were lucky to get a historical building at the De La Salle College as the primary location. I’m still grateful to the college and the Chaotic Board for being welcoming and generous to us.

When my director of photography John Holosko CSC and I walked into the premises of the filming location, we knew instantaneously that the building would be the character in the film. As much as I wanted to break out of the unity of time and place, I had to stay fateful to the original text, picturing the world as a madhouse in a small box.

John understood the analogy of this film very well, so I gave him an open palette.. He used classic three-point lighting throughout the film as if communicating with this magnificent old building. The Swedish chapter of the European Society of Cinematographers, FSF Sweden, complimented John’s work, comparing his lighting technique to legendary Sven Nykvist’s work. https://fsfsweden.se/john-holosko-csc-unique-lighting-strategy-for-nursery-rhyme-of-a-madman/

9. How did you choose the soundtrack of your film?

Every detail in this piece calls for a style as the story is happening in some unknown place, somewhere between the past and present. The music had to support and more over emphasize the film’s mood. Vivaldi was an excellent choice for the most part, but we were looking for someone more contemporary to complement the classic compositions. I asked my friend, a talented music composer, Jason Greenberg, for help. Before going into hard work, Jason suggested that we look into his extensive catalogue of music scores, available for licensing. We have found a perfect match for the main theme, the song Anna by Adrian Sood. It conveyed a mysterious dark tone that would turn into a mesmerizing legato. It practically describes our character, also named Anna, as innocent, pure and beautiful but trapped in a dark place looking for light.

10. What would you say have been some of the biggest surprises or challenges in this process? Do you have any funny anecdotes from the production to share?

It was almost undecided if we were pursuing this piece as a horrific drama with elements of sarcasm or a thriller with moments of dark humour. As we moved along with blocking and rehearsals, we all gravitated toward absurdity.

On the first day, we shot the runaway scene with Anna pushing Mitchel in the wheelchair. The front wheels got stuck in the soft grass, and the wheelchair tipped over. The poor poet ended up face down on the ground, not moving. A production assistant near me ran to help him, but my hand grabbed her sleeve. Everyone around screamed, “No! Don’t spoil the shot!” We were all on the same page. Even our actor, Chris Rika, happily smiled with mud on his face. There was no way back. The film had to be a dark comedy.

11. When working on a film, do you like to collaborate with the same cast and crew, or do you prefer to start fresh for each project?

I’m generally loyal to the people I work with. I love my actors but am also excited to meet new talents.

I was lucky to have known most of our actors for some time and worked with them in a few theatre plays, short films and TV shows. We created an ensemble under the umbrella of the Toronto Theatre Academy, led by a fantastic acting coach and talented art director Tim Kachurov, who played Dr. Groom in our film.

We were down one cast member in the middle of the shoot and had to find an actor to play Professor Woldorf asap. We were lucky to get Peter Hodgins to fill in and take the role. We met him for the first time, and he did an excellent job.

Working with a crew is different. We constantly had dailies, but permanent crew members supported them. It’s good to have some old contact in new projects, to maintain the stability and harmony of the production. It’s much easier to work in cities like Toronto, New York or LA, where you have facilities and a big pool of people to help you.

On the other hand, when writing and developing a script, I find it refreshing to have new members join in. New people often bring new ideas. In addition to writers I know in Toronto, I was lucky to meet a fantastic script consultant, Pilar Alessandra, at one of the DGC seminars. She helped me from her base in Los Angeles improve our story.

12. If you got the opportunity to remake a classic, which one you go for?

I can not find fulfillment in remaking films already done. Partially, I see it as an insult to someone else’s vision, and I wouldn’t feel a creative challenge to recreate someone’s work. In the ideal world, the genuine director’s job is to look for sources from life, art and literature, not challenging, copying, or correcting other filmmakers. The industry may sometimes have different needs, but that’s work that no director wants to refuse.

13. Toward the end we see Nurse Anna bringing Mitchell outside the asylum. What does the rainbow that we see at the end of the street, which is also the only bright colours we see through the movie, represent?

The rainbow on the tunnel was not in the script. It was already there waiting to meet us. Crossing the bridge and approaching the tunnel painted in rainbow colours foreshadow Mitchell’s and Anna’s deliberation. I didn’t mean to be illustrative, but “unicorns” and “the light at the end of the tunnel” is good to have, even if it feels like a cliche for a happy ending.

Most filmmakers find happy endings a bit corny, but the cornier it is, the happier we are.

14. What are you working on right now?

I’m between a few projects in development.

One is a social drama called “Unwanted,” involving the trafficking of children based on actual events. It will be a coproduction, and I hope to present it to Telefilm Canada by the end of the year.

The next one is “Joni Goes Postal,” written by Joan Wannan. It’s a comedy/drama about a postal worker who discovers her long-term boyfriend cheating. Heartbroken, she goes “postal .”A series of silly situations and masterminded acts of revenge help her to realize that her life is better without him.

We are still in negotiation to put “Cake” into development. It’s a dark comedy/ thriller written by the filmmaking veteran Allan Moyle. It’s a self-actualization play-like drama about a model photographer confused by his values and choices in life. As his past returns to hunt him, the circle closes on him in just one night.